The practice of hospitality is one of the oldest and long-lasting human societal behaviors. In early tribal cultures, hospitality was a method of ensuring mutual safety in an unsteady world, a code of conduct that guided people to treat strangers with respect and courtesy upon first meeting rather than hostility. Hospitality is one of the many mechanisms societies use that enable people to live together peacefully. Sometime a lost art in a world that encourages suspicion and fear of the “other”, hospitality is essential to having a functioning, healthy, and safe community.

One of the defining aspects in my experiences in Ireland was the overwhelming sense of welcome that we received everywhere that we went. It is clear that hospitality is a cultural reality to the Irish people. Historically, the Brehon Laws defined strict and clear rules of hospitality for both hosts and guests to follow and these rules were more than just guidelines. The laws of hospitality were obligations that the rulers were stringently held to. Failure of hospitality was a grave offense for a king to be accused of, and it could signify the end of their reign.

It would be difficult to find a more fitting symbol of Irish hospitality than the image of a pint of Guinness. It’s a beer and a brewery that is synonymous with Ireland. Along with the Irish people, Guinness has spread around the world and its popularity and reach is a testament to the enduring and endearing quality of Irish hospitality.

So when the rest of the tour arrived in Ireland, one of the first stops that we made was to the Dublin tourist Mecca of the Guinness brewery. I had expected this to be a simple stop, a trip to the well spring of what I would have to call my favorite beer. What we didn’t expect is a visit from the Dagda during our visit there.

The Dagda is a unique and quintessentially Irish God. While many of the Irish Gods have continental cognates, Gods that have similar linguistic counterparts in other Celtic cultures, the Dagda stands alone, exclusively Irish, as ancient as the standing stones and passage tombs.

The tales of the Dagda run alongside the major tales of Ireland, influencing the major events but also extending beyond them as well. The Dagda tracks across Irish history and legend, shaping the land, insuring victory for his tribe, altering time and space, and using law and language to trick others and get his way when he needs to.Rough, undignified, and often considered vulgar to the sensibilities of the Victorians that were recording the tales of the medieval monks, the Dagda means the “Good God”, not good in the moral sense, but meaning skilled at everything. As the keeper of the Cauldron of the Dagda, one of the four treasures of the Tuatha from which no company would ever leave from unfulfilled, He is deeply connected with the concept of hospitality.

As we entered the massive brewery, it was clear that this was somehow the Dagda’s place. He sidled up to us during the tour with a variety of requests: “Grab a handful of that barley” “Get a closer look at that harp for me” “That’s a beautiful glass, I would like one”. He walked with us, beaming with pride at the scope and size of the establishment, a pride that we assumed was just a natural delight in the national beverage of his land.

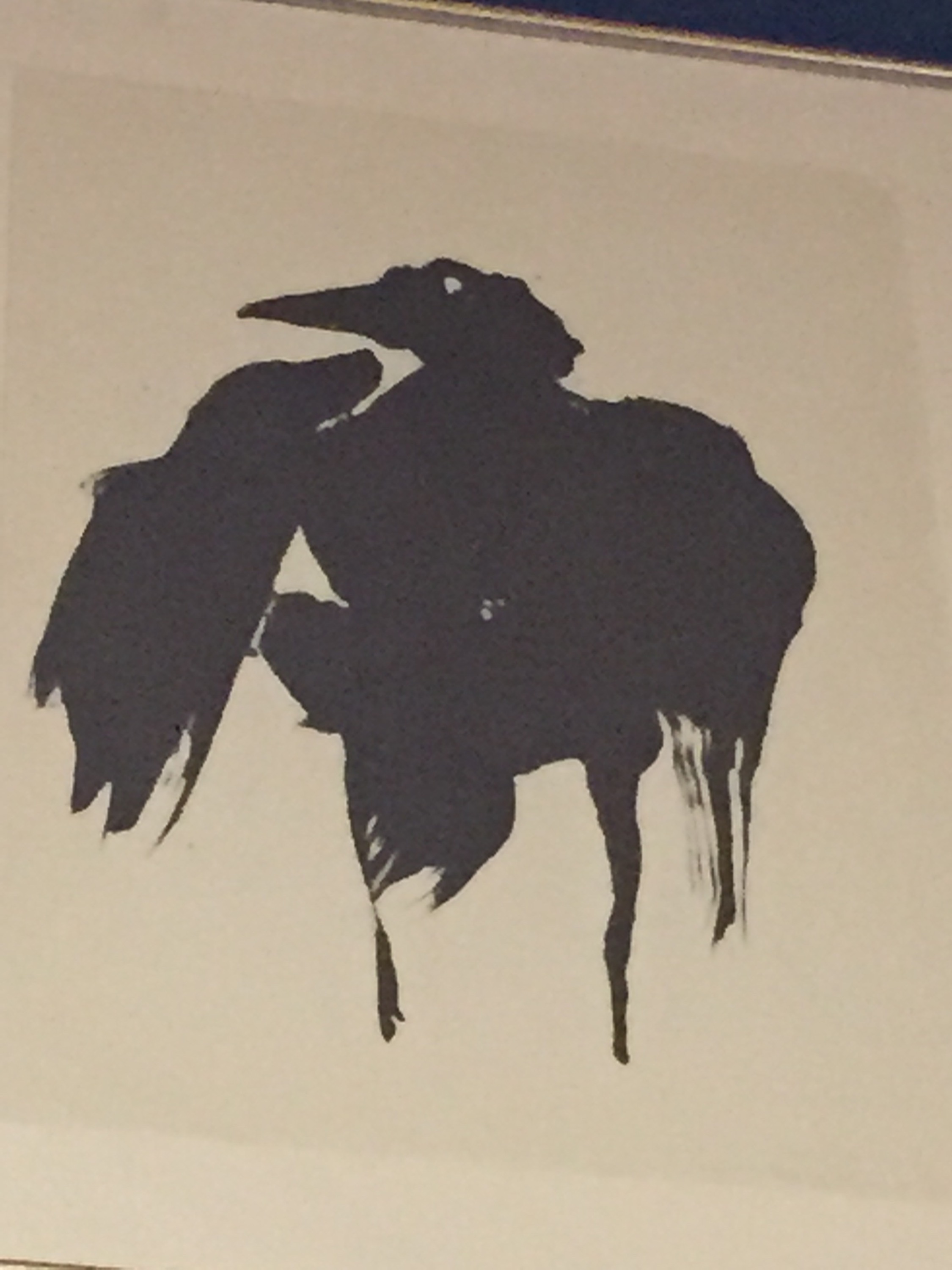

Days later, during our trip to Brú na Bóinne and Newgrange, as we were telling stories of that place and of the Dagda and Boann and Aengus their son, our coach driver and guide, the mighty Druid of the Coach John Byrne (Sean O’Broin) told us a bit of history of the name Guinness. John told us that the name Guiness is actually an anglicized version of the name Mac Aengus (or Mac Óengus), meaning “Son of Aengus”.That bit of information hit us all immediately, of course the Dagda was present at the Guinness brewery, it is likely that it is his family’s business. As we thought about this idea, a number of connections became evident to us. The giant pint glass shaped structure that the brewery is built around as a reflection of the Cauldron of the Dagda, the symbol of Guinness, the Harp of the Dagda, the role in promoting Irish hospitality that Guinness plays, even the most common way the Dagda trick people and gets his way, through the manipulation of time and legal language evident in the 9000 year lease that Arthur Guinness secured for the location of that compound at St James Gate, Dublin, a lease that is built into the foundation of the brewery itself.

So that first day of the Coru’s tour of Ireland, we stood in the Gravity Bar of the Guinness Brewery looking out over a 360 degree view of that beautiful grey city and we raised a glass to Dublin, to Ireland, and to the Dagda, father of hospitality, master of the harp, and shaper of the land.

Poems for the Dagda

by Scott Rowe, Coru Priest

Good God of the mighty appetites

Your skill and prowess bring us awe

Dagda, play a lay upon your harp

So that the seasons go on for us all

Your life-giving club

Bringing ecstasy, full of joy

Leave your mark upon the Land

That Her cries of ecstasy bring victory

Victory without conquest

Conquest overturned

A tune of liberation

Libations poured out

Bellies very full

Cups full of drink

Drinks with comrades

The gifts of the Dagda

Hard work, labor’s end

Joy in the doing

A sheen of sweat upon his brow

Buttered porridge and beer awaiting

Cock and belly, club and cauldron

None leave them unsatisfied

Inspiration of the harp

Righteous battle is coming